Literary Critic and Poet

TED HUGHES

Ted Hughes: A Bibliographical Supplement 1996-2013.

In 1983 Stephen Tabor and I published the first authorized bibliography of Ted Hughes, up to 1980. It was awarded the Library Association's Besterman Medal as the best bibliography of that year. In 1998, just in time for Ted to see it, Mansell published a new edition updated to 1995 and twice the size. That second edition has been long out-of-print (though I can supply copies for £50). Many works by Hughes have been published since his death, and critical works about him have burgeoned worldwide. This 88-page supplement contains a new section on theatrical productions of his plays.

Michael Daley

Natural Man: Collected Essays and Talks on Ted Hughes.

In 1802 Coleridge feared that by ‘abstruse research’ he had stolen from his own nature ‘all the natural man’*1. What he saw as a unique and culpable crime was to become, without the need for abstruse research, a common feature of the Modern Age - alienation. The increasing tyranny of the left hemisphere of the human brain was already driving the Mammon-worship of capitalism, the industrial revolution, the depopulation and pollution of the land, the degradation of the lower classes in cities, the rabid exploitation of children, animals, the whole natural environment. In 1970 Hughes wrote of the exile of man ‘from both inner and outer nature’:

The story of the mind exiled from Nature is the story of Western Man. It is the story of his progressively more desperate search for mechanical and rational and symbolic securities, which will substitute for the spirit-confidence of the Nature he has lost.*2

The hundred and seventy years between Coleridge and Hughes had seen this process accelerate out of control:

The later phase has become vastly complicated, and involves the salvaging of all nature from the pressures and oversights of our runaway populations, and from the monstrous anti-Nature that we have created, the now nearly autonomous Technosphere.*3

In the sixties Hughes’ own sense of exile from Nature had driven him at times close to Coleridge’s dejection and Beckett’s nihilistic absurdism. But in the seventies he recovered his commitment to nature and the natural man:

Society is in perpetual turmoil with the efforts of this huge suffering lump of vital shut-away truths to escape and speak, and with our efforts to release it and hear it.*4

This was Hughes primary effort as a poet, to discover and give voice to these truths, to identify the split within himself and use art, the body’s psychic immune system, to try to heal it. He believed that if the poet can heal himself, that healing power can be transmitted through the imaginative experience of reading the poems, to the psyche of the reader. He was well aware, however, that in our society the poet who answers such a call is taking on something very difficult, and perhaps impossible: ‘Everything among us is against it’.*5

I have traced this process in three books, The Art of Ted Hughes (1978), The Laughter of Foxes: A Study of Ted Hughes (2000) and Ted Hughes and Nature: ‘Terror and Exultation’ (2010). It is also a recurrent theme in the scattered essays and talks I have gathered here.

1 Dejection: An Ode’.

[I do not advise reading all the following pieces at one time, because of the amount of repetition.

Diverse essays and talks on the same author are bound to overlap. I learned long ago that one cannot expect readers or listeners to have read all one has previously published. Alternatively, you can work on the principle that what I tell you three times is true.]

| Download | |||

| 1 | Ted Hughes and his Landscape. First published in Poetry Wales, 1980. | Word | |

| 2 | Ted Hughes and William Blake. A paper given at the first international conference on Hughes, Manchester, 1980. First published in The Achievement of Ted Hughes, ed. Keith Sagar, Manchester U. P. 1983. | Word | |

| 3 | The Evolution of ‘The Dove Came’. A paper given at the second international conference on Hughes, Manchester, 1990. First published in The Challenge of Ted Hughes, ed. Keith Sagar, Macmillan, 1994. |

Word | |

| 4 | ‘The Poetry Does not Matter’. First published in Critical Essays on Ted Hughes, ed. Leonard Scigaj, G.K. Hall, 1992. |

Word | |

| 5 | From World of Blood to World of Light. First published in Moulin, Joanny, ed. Lire Ted Hughes: New Selected Poems 1957-1994. Paris, Editions du Temps, 1999. | Word | |

| 6 | The Mythic Imagination. First published in The Laughter of Foxes, Liverpool University Press, 2000. |

Word | |

| 7 | Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath: From Prospero to Orpheus. First published in The Laughter of Foxes. |

Word | |

| 8 | The Story of Crow. First published in The Laughter of Foxes. | Word | |

| 9 | Burning the Heart. [Review of Ted Hughes: Collected Poems] First published in Resurgence, March/April 2004. |

Word | |

| 10 | Ted Hughes: Visionary. First published in Visionaries of the 20th Century, Green Books, 2006. |

Word | |

| 11 | Ted Hughes and the Calder Valley. A talk given to the Hebden Bridge Local History Society, October 2008. Unpublished. |

Word | |

| 12 | Ted Hughes, Fishing and Poetry. A talk given to the Elmet Trust, October 2009. Unpublished. |

Word | |

| 13 | ‘Straight oxygen’: Ted Hughes and D. H. Lawrence. First published in the Journal of D. H. Lawrence Studies, vol.2 no.1, 2009. | Word | |

| 14 | Ted Hughes: ‘The Thought-Fox’. First published in Ted Hughes and Nature: ‘Terror and Exultation’, Fastprint Publishing, 2009. |

Word | |

| 15 | Ted Hughes and the Divided Brain. A talk given at the International Conference on Ted Hughes, Pembroke College, Cambridge, September 2010. First published in the Journal of the Ted Hughes Society, no.1, Summer, 2011. |

Word | |

All these essays are © Keith Sagar 2012. They may be quoted within the limits of fair dealing, and with due acknowledgement to this website,

Poet and Critic: The Letters of Ted Hughes and Keith Sagar,

Edited by Keith Sagar. The British Library, May 2012.

The friendship between Ted Hughes and Keith Sagar lasted from 1969 until Hughes’ death in 1998. During that time Hughes wrote 145 letters to Sagar, probably the most important correspondence ever between a great writer and a critic. Roy Davids has described it as 'the finest commentary taken as a whole by Hughes on his own work'. Their relationship, however, extended to many areas beyond literature, and the letters also cover such topics as Hughes' travels, his opinions on the royal family, hunting, religion, education, and his relationship with Sylvia Plath.

The friendship between Ted Hughes and Keith Sagar lasted from 1969 until Hughes’ death in 1998. During that time Hughes wrote 145 letters to Sagar, probably the most important correspondence ever between a great writer and a critic. Roy Davids has described it as 'the finest commentary taken as a whole by Hughes on his own work'. Their relationship, however, extended to many areas beyond literature, and the letters also cover such topics as Hughes' travels, his opinions on the royal family, hunting, religion, education, and his relationship with Sylvia Plath.

‘That Keith Sagar was engaged with Hughes in such a correspondence for nearly thirty years, and in such detail, is a measure of Hughes’ trust and of how constructive and fortifying he found their exchange,’ John Moat.

The book contains a long introduction, and the whole of Hughes' letters to Sagar, interspersed with extracts from Sagar's letters to Hughes.

Reviews

The letters, which span nearly 30 years, begin as courteous communications from a poet to a critic he barely knows but develop into a series of extraordinary revelations from an intensely private man to a trusted friend. For the poetry enthusiast, they are dynamite.

Christina Patterson, Guardian.

Charting a friendship of almost thirty years, the correspondence is an unexpected literary treasure .. and an essential addition to Hughesian scholarship.

Terry Kelly, London Magazine.

Sagar's admiration and loyalty to the poet shines through; likewise for Hughes, and I have learned a completely new side to him. This dedication to the art and craft of poetry is evident throughout the book, and is certainly one of its many achievements. This is a valuable book for readers of 20th century poetry and educators; for rare book and manuscript collectors; and for enthusiasts of the drama called life, among others.

Peter K. Steinberg.

This excellent edition is essential reading for anyone interested in Hughes' work, whether general reader or scholar. Not only do the letters give a fascinating insight into the man behind the poems, the work itself is often foregrounded. This corresponence illustrates how the very best and engaged criticism fully serves to widen appreciation of the art. There is no academic sterility to be found in their exchanges; Hughes' oeuvre comes more fully alive. What a wonderfully produced book this is, beautifully designed, and with great photographs.

Matthew Howard.

TED HUGHES AND NATURE:

TED HUGHES AND NATURE:

‘TERROR AND EXULTATION’

In Memory of Ted Hughes (died 28 October 1998)

A ghost crab sidled into his body

By moonlight

Laid its thousand eggs.

*

When that oak fell a tremor passed

Through all the rivers of the West.

The spent salmon felt it.

*

A rare familiar voice

Entered the October silence

While red leaves fell.

Reviews

Time and time again, Sagar’s sensitive and empathetic readings have brought new insights into the poetry, and opened fresh ways of looking at the work of one of the major poetic minds of western literature. Difficult concepts, both intellectually and emotionally, are communicated in accessible, readable terms. Like so many of the poems, the awareness and understanding displayed are simultaneously life-enhancing, and humbling.

Roger Elkin

That Keith Sagar corresponded with Hughes for nearly 30 years, and in such detail, is a measure of Hughes’ trust and of how constructive, ultimately fortifying, he found their exchange. Sagar’s new book is the ultimate flowering of this trust. I can’t really see how anyone could find his or her way through the 1,300 pages of Hughes’ Collected Poems without it.

John Moat

Epigraphs

Art is the mediatress between, and reconciler of, nature and man.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

‘Virtue’, said Marcus Aurelius, ‘what is it, only a living and enthusiastic sympathy with Nature?’ Perhaps indeed the efforts of the true poets, founders, religions, literatures, all ages, have been, and ever will be, our time and times to come, essentially the same ― to bring people back from their persistent strayings and sickly abstractions, to the costless average, divine, original concrete.

Walt Whitman

We still talk in terms of conquest. We still haven’t become mature enough to think of ourselves as only a tiny part of a vast and incredible universe. Man’s attitude toward nature is today critically important simply because we have now acquired a fateful power to alter and destroy nature. But man is part of nature and his war against nature is inevitably a war against himself.

Rachel Carson

The natural world, in virtue of its very being, bears within it the presupposition of the absolute which grounds, delimits, animates and directs it, without which it would be unthinkable, absurd and superfluous, and which we can only quietly respect. Any attempt to spurn it, master it or replace it with something else, appears, within the framework of the natural world, as an expression of hubris for which humans must pay a heavy price, as did Don Juan and Faust.

Vaclav Havel

The story of mind exiled from Nature is the story of Western Man. … When something abandons Nature, or is abandoned by Nature, it has lost touch with its creator, and is called an evolutionary dead-end. … When the modern mediumistic artist looks into his crystal, he sees the last nightmare of mental disintegration and spiritual emptiness. … But he may see something else … the vital, somewhat terrible spirit of natural life, which is new in every second. Even when it is poisoned to the point of death, its efforts to be itself are new in every second.

Ted Hughes

The poetry of Hughes has brought us, in the most exact sense, closer to nature, its complex workings, than any English poet we can think of … It is a poetry of exultation.

Derek Walcott

Preface

The centrality of nature in Hughes’ work has been obvious from the publication of The Hawk in the Rain over half a century ago, and much has been written on it. However, it has seemed to me in recent years that critical commentary on this essential theme, including my own, has remained fairly superficial. The main purpose of this book is to try to take it, in several ways, onto another level. The publication of Hughes’ letters in 2007 has given us the opportunity to relate his poems more closely to his life and reading; but I also wanted to give it a larger context by relating it (as Hughes himself did so often in his prose) to the whole history of our relationship with nature since the dawn of civilization, and the tradition of nature-poetry in English.

We know that Hughes had a very good education at Mexborough Grammar School and Cambridge, that he received much encouragement from his mother and sister, and that he read voraciously beyond his school and university syllabuses. Thus most of the literature I have discussed in the first chapter would have been familiar to him by the time he graduated, and hugely influential. However it seemed to me useful to try to distinguish between those influences which were part of our common cultural and literary inheritance, in the first chapter, and those which were more specific to Hughes in the second. I have obviously made no attempt to discuss, or even list, all the influences I am aware of, which would themselves have been only a tiny proportion. I have concentrated on influences specifically on Hughes’ poetic response to nature, and on those influences he seems to have been himself most aware of.

***

Many years ago I devised a course for my adult students called Orientations in Modern Literature. The idea was to attempt to locate each writer on a compass, on which the cardinal points would represent the four basic attitudes to nature which seemed to me to be possible. The allocation of points to attitudes was arbitrary, but had some slight logic. North, being bleak, I assigned to the belief that life is nasty, brutish and short, meaningless and irredeemable. One writer who could be located here is obviously Samuel Beckett. South, representing the warmest and most affirmative position would stand for the opposite belief, that life is wonderful, perhaps sacred, and either self-redeeming or not in need of redemption. Here I placed (provisionally) D. H. Lawrence. The belief that life on earth is not the ultimate reality, and that it needs to be redeemed in terms of a purely spiritual reality outside time and space, I allocated to East, since we associate the east with mystical and transcendental thought. Here I placed the Eliot of the Four Quartets. The West we associate with rationalism, secularism, science; with the view that the defects of nature can be mitigated by political and social action, that civilization can gradually improve the world. Here I placed Brecht. Many writers, of course, would need to be placed at intermediate positions.

What proved most interesting about this scheme was the demonstration of

how many of the great writers in the course of their careers moved significantly around the compass. (Shakespeare seems to have occupied every possible position at one time or another.) Hughes is particularly interesting in this context since he moved from north via east to south, but in doing so did not betray the harsher truths by sentimentality or by succumbing to the glamour of the universe. He strove rather to hold together Coleridge’s vision of Nature as ‘the wary, wily old long-breathed witch, tough-lived as a turtle’ with the claim that she is also ‘Heaven’s Mother’, her undeniable role as ‘the putrefying oceanic grave’ with he equally, for him, undeniable role as ‘the radiant cauldron of abounding new life, the river of erotic song and the sacred word’ [Winter Pollen 440].

In his 1970 review of Max Nicholson’s The Environmental RevoutionI Hughes praised Nicholson’s ‘tremendous imaginative grasp of the true life of the earth, the inner spiritual unity of nature’. But he believed that poetry was the language best qualified to bring home to readers ‘the actualities of the earth’s life’ and the ‘inter-relationship of Nature and the inmost psychology of man’ in such a way as to permanently affect the reader’s own vision, and that became the ultimate objective of his own poems. Yet only ten years earlier Hughes had described nature as ‘brainless & the whole of evil’. This transformation needed to be documented and accounted for. Hughes’ negotiations with nature are inseparable from his simultaneous dialogue with all the earlier writers who had undertaken similar negotiations.

***

Book-length critical studies of Hughes’ poetry began to appear before the mid-point of his career. The downside of this early recognition of his importance was that a view of Hughes as a poet began to consolidate based, of necessity, on his early work. Later studies were of course able to add chapters on later collections, but the damage had been done in that many readers seem to have formed the opinion that Hughes had reached his peak in Crow (which was widely misunderstood) and that the later collections were either repetition or digression or decline, a decline dramatically reversed in his final collection Birthday Letters. A bias against or neglect of these is still widely evident.

I believe that Hughes’ finest and most important work, for which all the earlier books were preparation, is to be found in the three collections published between 1979 and 1983, Moortown, Remains of Elmet and River. Surprisingly, these collections have received far less attention than Hughes’ earlier and later work. Hughes’ poetic career is a continuum, each phase comprehensible only in terms of what had led up to it. Therefore I shall survey the core of that quest, his struggle to get into a right relation with the source, that is, with Nature and the female, from the beginning. Each collection is not simply a batch of his latest work, but a bulletin from the latest stage of an ongoing imaginative quest, which, after a phase of intense suffering following the tragic events of his life in 1963 and 1969, gradually succeeded in transforming that suffering into enlightenment. Hughes put himself in the dock in the shape of a succession of alter-egos, and underwent correction and rebirth.

Hughes believed that poetry is part of the self-healing equipment of the psyche; that if the poet, as Adam, as Everyman, can heal himself, that healing power can be transmitted through the imaginative experience of reading the poems, to the psyche of the reader. The great poems of the seventies and early eighties are the culmination of his quest. It is in these three collections that Hughes finally resolved the problems he had hitherto wrestled with in relation to nature and the female, and was able to worship the source of life in verse which is simultaneously radiant, yet rooted in the elements – air, stone, earth, water.

The poems collected in Moortown span the crucial period from the agony of the protagonist in Prometheus on his Crag, through the humility and acceptance of the farming poems, to the awakening of Adam to the limitations and potentialities of the human condition in Adam and the Sacred Nine. The epilogue poems in Gaudete have an importance extending far beyond the context of that book. Hughes’ discovery of vacanas released a vein of direct, powerful and personal verse which revitalized his subsequent work. Remains of Elmet is a lament for the cost of the Industrial Revolution both to the environment and to its inhabitants, but also a celebration of nature’s powers of regeneration. River, the acme of Hughes’ achievement, takes rivers to be the bloodstream of the goddess, Nature, and contributes more than any other collection to the respiritualization of a fallen world.

Almost all Hughes’ collections were very carefully planned, in accordance with some overview which had for him a specific mythic, or astrological, or alchemical, or cabbalistic significance. Since he knew that very few of his readers would be aware of any of this, he must have believed that such structures would have a subliminal influence on the reader’s response to the whole collection. Thus he regarded it as particularly important that his collections should have a positive, or, as he put it, ‘up-beat’ ending. There was, however, a price to pay for these imposed structures. For the sake of them Hughes can be draconian, distorting the original meaning of the poems to make them fit the postconceived pattern. They also frequently violate the chronology of the poems, and thereby distort or falsify our sense of Hughes’ development, of the relationship between the poems and the life. Hughes described his own poems as bulletins from the battleground of warring forces within him. It is surely important that such bulletins should arrive in the correct order. I shall therefore attempt to discuss the poems in as exact a chronological sequence as I can establish.

The attraction for him of all the structures and systems Hughes devised or exploited as frameworks for his poems was that they put a smokescreen between the life and the art, kept separate, as Eliot had required, ‘the man who suffers and the mind which creates’ [Selected Essays 18]. ‘It is not in his personal emotions, the emotions provoked by particular events in his life,’ Eliot wrote, ‘that the poet is in any way remarkable or interesting’. Poetry, he claimed, was an escape from emotion and personality. In later years Eliot came to admit the hypocrisy of those claims, when he described ‘The Waste Land’ as ‘a wholly personal grouse against life’. Hughes needed such an escape even more than Eliot, but after Cave Birds his poems become more personal, more keyed to the events of his life, the daily struggle of farming in Moortown Diaries, his recovery of his own childhood world in Remains of Elmet, and his revitalizing encounters with the very body of the goddess in River.

Ted Hughes and Nature: ‘Terror and Exultation’ is available as a paperback at £9.50 from www.fast-print.net/view.php?book=538

The

Laughter of Foxes

The

Laughter of Foxes

(Liverpool University Press, 2000)

The Laughter of Foxes surveys the whole of Hughes' achievement, not only in verse. It contains a great deal of new information, including extracts from Hughes' letters to the author, a detailed chronology of his life and work by Ann Skea, and the first publication of the background story of Crow. There are chapters on the mythic imagination, the poetic relationship of Hughes and Plath, and on the evolution of a Hughes poem through all its manuscript drafts. But the main purpose of the book is to attempt an adequate reading of Hughes' poetry, revealing the underlying quest which transformed his imagination, leading him by painful stages from a vision of a world made of blood to a vision of a world made of light.

'This book is invaluable for anyone interested in Hughes' work'

Elaine Feinstein Daily Telegraph

'Sagar's strength is his ability to appreciate from the inside the mythic journey which Hughes was undertaking through his work. Sagar's fine and sensitive book is proof that penetrating critical thought can be couched in lively and readable prose'

Erica Wagner The Times

'In an age when most of what passes for literary criticism is of interest to no-one but initiates of its own scarcely penetrable codes, here is a book which continually reminds us what an enlarging joy and privilege and challenge it is to read the work of a master-poet. In doing so, it performs a valuable service both to its subject and to the wider evolution of consciousness in our time. Whether poetry matters to us or not, the responsibility remains with each of us to bring to our lives the highest degree of ethical commitment and imaginative energy of which we are capable. And in that struggle, as the life and work of Ted Hughes so magnificently demonstrate, poetry can be far more than the consolation of an idle hour: it becomes a vital source of transforming energy'

Lindsay Clarke Resurgence

'The Laughter of Foxes undertakes the necessary labour of fitting to the poetry the paradigms worked out in Hughes' fascinating mytho-critical prose from the 1990s. ... The central chapter, 'From World of Blood to World of Light', convincingly plots Hughes' progression towards a potentially redemptive vision.'

Jeremy Noel-Tod Times Literary Supplement

This book can be ordered from The Times online bookshop

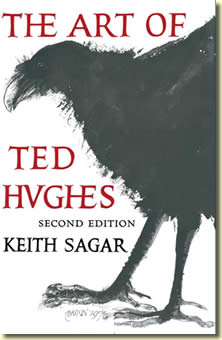

The

Art of Ted Hughes

The

Art of Ted HughesDr Sagar believes that when we see Ted Hughes' work as a whole, with each book a stage in a psychic adventure involving new stylistic challenge, we shall see it to be the achievement of a major poet. In this study of Ted Hughes, Dr Sagar gives most of his attention to individual poems, their meaning and coherence, their relation to each other and to the poetic tradition, their sources and background (often in mythology and folklore), and their relevance to living in our time. He began reading Hughes in 1957 when The Hawk in the Rain appeared, and has followed his development closely ever since: here, with benefit of hindsight, he attempts to retrace that journey. A chapter is devoted to each major work.

Since the first edition of this book appeared in 1975, Hughes published three important collections. Season Songs in 1976, Gaudete in 1977, and Cave Birds in 1978. All represent important stages in Hughes' development. For this second edition, Dr Sagar added a chapter on each of these, revised the earlier text, and brought the comprehensive bibliography up to 1978.

'Sagar is a convinced and, on the whole, convincing reader of Hughes' poems; he thinks they are among the superior achievements of modern poetry ... I am glad that Sagar's book will raise questions that are crucial not only to the reception of Hughes' poetry but to the definition of contemporary English feeling.'

Denis Donoghue, New Republic

First Editions

I have most of Hughes' first editions for sale, including limited editions. For further details, postage, and availability of other titles, please e-mail Keith Sagar at keithsagar1@gmail.com

Books by and about Ted Hughes

[Bibliographical references are to Sagar and Tabor, Ted Hughes: A Bibliography 1946-1995, Mansell, 1998]

A1a The Hawk in the Rain, good, £100.

2nd impression 1960. Sound, clean library

copy in bright d.w..

£50

A12a1 Wodwo. Sound, clean library copy with

bright but very slightly torn d.w. in glacine

cover.

£25

A23b. The Tiger’s Bones, Viking 1974. v.g. in

d.j.

£10

A25a1. Crow, 2nd printing 1970. v.g. with fine d.w.

£50

A29. Poems: Hughes, Fainlight, Sillitoe,

Rainbow Press, fine in slipcase. Signed by the three poets.

£400

A46b1. Cave Birds, Faber 1978. Illustrations by

Leonard Baskin.

fine in DJ.

£50

A51a1. Gaudete, Faber 1977. v.g. in DJ.

£50

A54b. Moon Bells, Bodley Head 1986. Fine in

d.j.

£5

A59. Adam and the Sacred Nine, Rainbow Press,

fine in slipcase. Signed.

£200

A83. Weasels at Work, Morrigu Press 1983.

No.

15 of 75. signed,

£275.

A101. Reckless Head, broadside, Turret

Bookshop, 1993.

Mint. £50.

Tales from Ovid, Faber 1997. Boxed. Signed.

Perfect. £300.

Farrar Strauss and Giroux, 1997,

Hardback, fine in D.J.

£10

Birthday Letters, Faber 1998, fine in DJ.

£40

The Mermaid’s Purse, Faber 1999. Fine. D.J.

£5

Collected Poems. Faber 2003. Boxed ed. Limited

to 200.

Mint. £200.

Ted Hughes: A Bibliography 1946-1995. New.

470 pp.

£25.

Carey, ed. William Golding: The Man and his Books. Fine in d.w. Contains Hughes: ‘Baboons and Neaderthals: A Rereading of The Inheritors’.

£10

Sagar, The Art of Ted Hughes. 2nd ed. 1978.

CUP. 2008 reprint.

New. £15

Sagar. The Laughter of Foxes: A Study of Ted Hughes. Paperback. 2000.

New. £10

Sagar. Ted Hughes and Nature: ‘Terror and Exultation’. Paperback. New. 2010. £7.50

Sagar. Literature and the Crime Against Nature. Hardback. 2005. New. £15.

Exhibition catalogues £1.

An exhibition in honour of Ted Hughes, Ilkley Literature

Festival, 1975.

Illustrations to Ted Hughes Poems, Victoria & Albert

Museum, 1979.

The Art of Ted Hughes, City Art Gallery, Manchester,

1980.

These prices do not include postage.

Links

The Ted Hughes Society and Journal: www.thetedhughessociety.org

An international Hughes website is run by Claas Kazzer from the University of Leipzig.

For information about Hughes activities in the Calder Valley visit www.theelmettrust.co.uk.

Ann Skea has her own excellent Hughes website.

site created by The Word Pool